Frustrated by the lack of affordable housing, middle-class workers are giving up on Issaquah

When Kat Wilkins moved to the Eastside a year and a half ago, she thought the cost of living in the area couldn’t possibly be more expensive than where she moved from, California’s Sonoma County.

But with a monthly budget of $800 for housing, almost 50 percent of her income, Wilkins never bothered even looking in Issaquah, where she works for one of the city’s largest employers.

The first place Wilkins considered was in Carnation, but the winding back roads between the towns and the long commute wasn’t appealing.

“I didn’t think I would have a hard time,” Wilkins said about her search for a home. “But it’s crazy expensive.”

She eventually secured a room in a large house in Snoqualmie with seven other roommates.

“I’m 55, I want my own place, but if you can’t afford it, you can’t afford it,” Wilkins said.

A few months later, a new position and a small pay increase at work allowed her to shed those seven roommates.

Though finally on her own, each month the $975 in rent she pays is still almost 40 percent of her monthly income. It gets Wilkins the downstairs portion of a house she rents in Renton.

Her commute distance hasn’t changed. The roughly 12 miles to and from Issaquah can take Wilkins as little as 20 minutes, but come rush hour, the travel times double or even triple. With her 1 p.m.-to-9 p.m. shift, Wilkins usually misses the afternoon rush hour that paralyzes the city.

“It’s expensive, but I’m on my own,” Wilkins said. “Why can’t they bring the rents down so people can afford to live here?”

Two affordable homes in six years

More than 1,000 units of housing — homes, apartments, condominiums — were built in Issaquah over the last six years. Only two of those residences were classified as affordable, while rents and real estate prices soared.

The average home sales price jumped 40 percent in just the last five years, rebounding from a 2007 peak, according to data collected by ECONorthwest for the city. Rents over the same time have increased almost 30 percent.

In a city where more than a third of all households spend more than 30 percent of their income on rent, only 7.7 percent of the city’s total inventory of homes and apartments is subsidized affordable housing, according ECONorthwest’s research.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development considers these families housing-cost burdened. They are often unable to save for a rainy day, and a health crisis or unexpected car repair can put these households at risk of homelessness.

Priced out of the community

In May of last year, less than two months before her lease was set to expire, Sarah MacDonald’s landlord informed her that the rent for her Klahanie apartment would soon be rising 16 percent, pushing her monthly outlay for the two-bedroom apartment she shares from $950 per month to $1,100.

MacDonald, a Grand Ridge Elementary School teacher, didn’t want to leave the community she had become connected to over the previous 18 months, but she was forced to consider other cities outside the school district as her next home.

MacDonald’s landlord eventually cut the young teachers a deal, increasing the rent only 8 percent. But she worries the next time her lease is renewed she might not be so lucky.

“How ridiculous is it that we can’t live where we teach?” MacDonald asked.

MacDonald wouldn’t be alone if she was priced out of the community where she teaches. Roughly half of Issaquah School District teachers live outside the district, often in cities with lower housing and rental prices, according to data gathered by the Issaquah Education Association.

“A lot of teachers are leaving because they can’t afford to live here,” MacDonald said. “There’s a lot of turnover.”

Ron Thiele, superintendent of the Issaquah School District, told a group of Issaquah business leaders that the 2016-17 school year was the toughest staffing year in his career. At the start of the school year, 19 teaching positions remained open, the school district said.

“Much of our staff commutes in,” Thiele said. “That makes it less-desirable to work here.”

He blamed the cost of living, particularly the cost of housing, as the primary reason many teachers leave the district to teach elsewhere.

Wanting to invest in a home rather than renting, third-grade teacher Maddie Ebi and her fiance lived with her parents in Issaquah for a year to save money as they looked for a home. Together, the couple makes roughly the median household income in Issaquah, which by city estimates means the young couple can afford to pay up to $360,000 for a home.

However, only 25 percent of condos, houses or townhomes for sale in Issaquah are priced at or below $360,000, according to ECONorthwest’s data.

With fierce competition for that quarter of the housing market they could afford, Ebi and her fiance, broadened their search and wound up in Maple Valley

“It’s pretty affordable,” Ebi said of her new home, which is 19 miles from her job at Grand Ridge Elementary “A friend on Capitol Hill pays more in rent for her 500-square-foot apartment than we do for our mortgage.”

But lower home prices come at a cost. Each day, Ebi must make the long commute from Maple Valley to the Issaquah Highlands.

“It’s not too bad, but I don’t think it’s sustainable for a super-long time,” Ebi said about the drive, which can take her anywhere from 50 to 90 minutes to get home at night.

“I think in the long run I’ll look for (a job that’s) closer,” Ebi said.

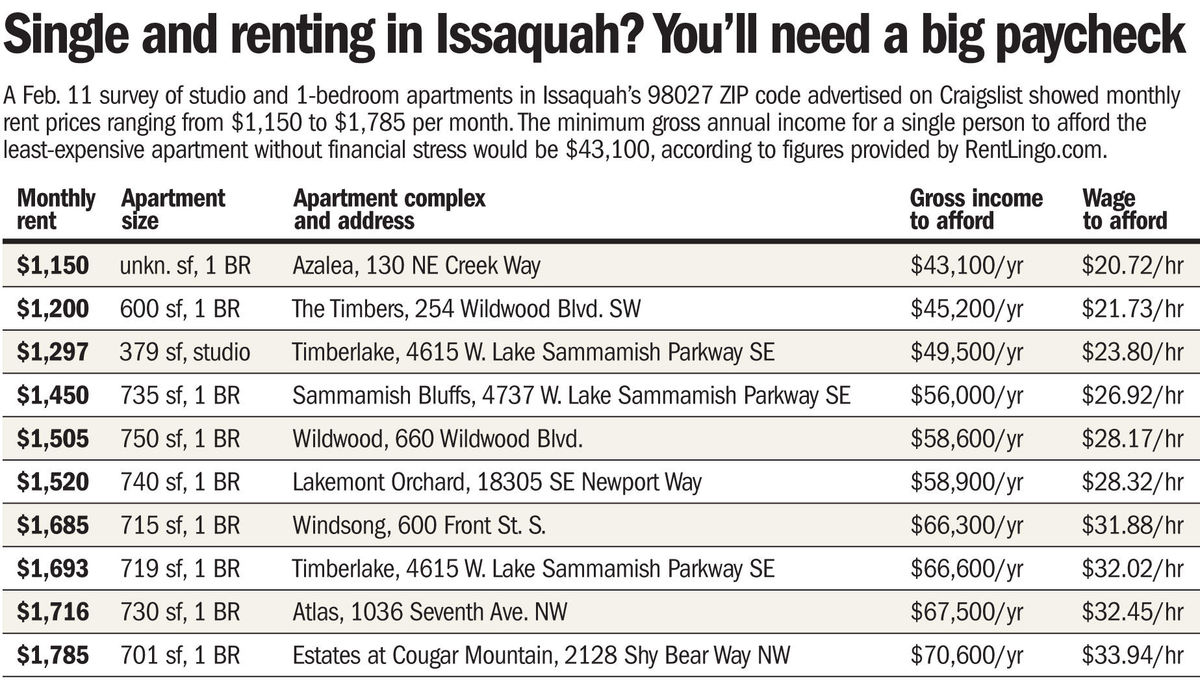

Of the 344 apartments constructed at one of the newest development in the city, none were within reach of residents making less than the median income. One-bedroom apartments can cost up to $1,800, which is the average rent in Issaquah. To afford that price without financial stress, a person or family needs to make at least $71,000 a year.

Squeezing out the middle class

Erin and Tyler Saldaña are part of the 5 percent of residents who both live and work in Issaquah.

Recently married, they moved to Issaquah at the beginning of 2015. The couple felt lucky to find an apartment in the Issaquah Highlands they could afford. It cost a little less than 30 percent of their combined income, but they were still managing to save a little from each paycheck.

As their job situations changed, the Saldañas wanted to downgrade to a smaller apartment but were unable to find a smaller and less-expensive apartment in Issaquah. Today, Erin manages a coffee shop in the city and Tyler works several part-time jobs.

More than half of the jobs in Issaquah are in fields that pay an average of $53,000 or less per year. With the average house price hovering around $700,000, homeownership here is out of reach for many people who work in the city.

Along with rising real estate values, developers are also building more expensive houses. Before 2000, a third of all houses, condos and townhouses built cost $360,000 or less. After 2000, that number drops to 11 percent.

Looking around at their co-workers, many who still live with their parents or live outside of town, the Saldañas think about returning to California, or at least leaving Issaquah.

“There’s no reason to stay,” Erin Saldaña said. “We are capped out. What else can we do? It’s only getting worse.”

Endless commutes

Kat Wilkins is one of 21,000 workers commuting into Issaquah each day, swelling the city’s daytime population by 20 percent. And with approximately 14,000 people leaving the city each day for their jobs elsewhere, Issaquah’s streets are overwhelmed.

At a regional transportation summit hosted by the city late last year, Mayor Fred Butler told a gathering of Eastside leaders and transportation directors that Issaquah’s traffic congestion had reached a crisis level because of pass-through commuters.

Long commutes leave workers less time to spend with their families or participate in their community, while at the same time increasing road congestion, according to Kelly Rider, government relations & policy director at the Housing Development Consortium Seattle-King County.

“When employees are able to live close to their work, they are more likely to reinvest their wages back into the community,” Rider said. “When they live elsewhere, the wages are being earned in one community but invested elsewhere.”

“It’s really hard here to be able to afford anything that is close to where you are working,” said Hayley Swanson, a 23-year-old third-grade teacher working in the Issaquah School District.

Last year, Swanson lived in a three-bedroom Redmond apartment with four roommates. She was paying less than $600 for her portion of the rent, but a move closer to her job came with a steep rent increase.

“For new teachers, it’s really hard to get on our feet,” Swanson said.

To adjust, she picked up extra work and canceled her gym membership.

“Living alone would be really nice, but it’s not something I can see myself doing,” Swanson said.

“Financially, I don’t see how I could live anywhere within a reasonable commute distance without a roommate.”

How to fix it?

A 2012 business survey showed 62 percent of local business said more affordable housing would be helpful to retain and recruit employees.

The Issaquah Schools Foundation is working on a plan to provide additional resources to the Issaquah School District for recruiting — and, more importantly, retaining — teachers.

“It’s a way to incentivize teachers to come and make it affordable,” said Kaylee Jaech, executive director of the Issaquah Schools Foundation. “Often the cost of living is so high (teachers) often end up moving out of the district.”

Partnering with Gary Young and Shelter Holdings, the foundation is hammering out the details on a program that would waive security deposits and administration fees on apartments owned by Shelter Holdings to anyone working for the school district. The foundation hopes to finalize the plan in the next month so it can be used as a recruiting tool when the school district begins hiring for the next school year.

“We have to put a stake in the ground and try something,” Jaech said. “This is just part of the answer. This is just another way that we are trying to convey to our teachers how important they are to us.”

Currently there is a three- to four-year waiting list for the Hutchison House Apartments, a 90-unit building near the intersection of Newport Way and Mountain Park Boulevard that is the one of the largest affordable housing community in Issaquah.

Hank Thomas, a former member of the City Council and a current board member of Hutchison House, wants to expand their nonprofit model to increase the supply of affordable housing in Issaquah.

He wants developers that build affordable housing to donate the apartments to a charity, removing the financial interest from the equation. That way, any profits can be put back into the affordable housing community instead of going to shareholders.

Thomas said it’s hard for a business to maintain low-income housing. “Eventually (the building) goes to market-rate or collapses all together,” he said.

“We need, together with our legislative group, to have a lengthy conversation and decide what is our responsibility when it comes to affordable housing,” Thomas said. “It will be an uncomfortable conversation.”

(6) comments

The Growth Management Act has created this problem, but there is no mention of that in the article.

free markets create winners and losers, and this is all about the law of supply and demand. with increased demand for housing, and a small supply of the same, the price of housing will increase to meet demand equilibrium. the city says to change this equation, just build more housing and that means more growth and more traffic. i seem to recall something on the ballot in november last year about that. the problem is the type of housing being allowed to be built - it's unaffordable housing! developers know what they have to collect in rents and sales prices of homes to make things profitable for them, and those prices are high enough that they are not affordable. what's the solution? the city needs to define what is affordable housing and what is low-income housing and _insist_ that developers build those types of housing - and if they don't - they can't build - period.

the other side of this discussion is what the commuinity wants - if issaquah residents do not want any more people coming to live in issaquah they will insist that no more housing of any type be built. then the price of existing housing will settle to meet demand - likely go quite higher. the answer may be to build housing and artifically keep the price low. not many developers will buy into that, which is where government in the past has come in to provide subsidies for those types of housing solutions. at stake with this issue are our community values and what kind of growing city we want to be. we all knew it would come to this.

Its seems this article was very teacher focused. I have worked in Sammamish and commuted from east Renton for 15 years. Most of the employees at my company can only afford to live in the outlying area. It isn't that bad of a commute. But I did want to note a couple things. Building affordable apartments do not solve the problem. When you stay at an employer long term you want to buy at some point. Not rent. Also, regarding the bad traffic. If there was bus service from affordable housing areas (renton, maple valley, etc) it would greatly alleviate the traffic problem. I looked into taking the bus to work and found that I would have to go all the way into Seattle and then back out to Sammamish. And then the bus to Sammamish (at the time) was only a commuter bus so if you worked any hours other than 9 to 5 it just wasn't possible. Anyway. That is my 2 cents on the situation.

I live over in Fall City and work in Seattle. I commute over an hour each way and I don't complain about it. I realize that I am not entitled to a house in downtown Seattle for the same price. That's not how life works. I moved farther out because I could get much more house for much less money. Issaquah is expensive. Taxes are unreasonably high. You either figure out a way to afford it or you don't. There are plenty of much more affordable places to live, literally next to Issaquah in most directions.

Sorry but this is entitled whining. There are plenty of places to live very close to Issaquah that are much more affordable. You either sacrifice your standards of living or your commute time. You can't always have everything you want

Thank you once again Liz for a good investigative report on the housing issues in Issaquah. One thing the City does not seem to understand is a lot of the traffic issue are a result of those minimum to moderately paid workers coming into Issaquah area add volumes to the vehicles numbers on our roads and also take up valuable parking space since there is not any real public transit options for most of the workforce.

When there is snow and ice on the roads the ISD district must decide how many of its teachers and support staff can even make it into work to open the schools at the same time they are deciding if it is safe for school buses to be on the roads and student to walk to their stops. In 201o when I was part to the Citizen Task Force making recommendations on how to plan for the Central Area I and others recommended the City partner with ISD and developers to plan for urban schools in the Central area which would have workforce housing next to or above the schools – so far nothing has been has happened to on the front.

Another issue that the City appears to be ignoring is the going number of senior care facilities that are going in out the outer edges of the City where there is no real transit service for the minimum to $15/hr care giver staff. Yet the City is allowing the minimum number of parking spaces thus making more of the workers who must drive trying to find parking on City streets and surrounding neighborhoods and or the visitors to their family members having to do so.

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.